By Tim Hennessy /

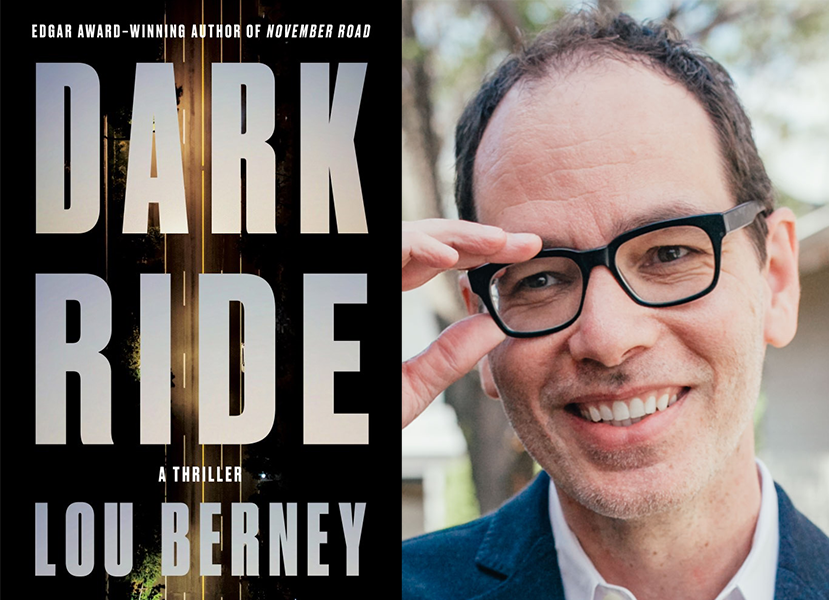

Early on in Dark Ride, Lou Berney’s endearing comedic-thriller (following the award-winning November Road), we are introduced to Eleanor, a goth receptionist in the Driver Improvement Verification office. She asks Hardy “Hardly” Reed why he’s interested in locating a woman who a day earlier left her children to wait on a bench outside while she was in the office. If he has suspicions that the children are being abused, why doesn’t he leave things to Child Protective Services as she suggested?

“I went by yesterday and it was kind of a clusterfuck,” he tells her. “I’m worried they won’t investigate what’s happening to those kids I saw. Or they’ll start too late. Or mess it up. So I’m thinking maybe I can…help.”

When Hardly first picks up on the situation, he’s in the building, trying to decide which of his multiple parking tickets he should pay or delay. He notices the two young kids, Pearl and Jack, sitting by themselves, appearing largely ignored and out of place. Unsettled by their detached demeanor and striking thinness, Hardly tries to strike up a conversation with them and observes what appear to be cigarette burns on both children. Hardly immediately knows something is wrong; confirming his suspicions, their mother returns, and he witnesses her rearrange the boy’s shirt to conceal the marks as she hurries them to their car.

Hardly knows something is wrong.

Like most of his friends and allies throughout Dark Ride and Hardly himself, Eleanor is dubious of his qualifications. “You are going to investigate and look for evidence?” she asks. “That is the most delightfully hilarious thing I’ve heard in ages.” Nicknamed by his foster brother for his lackadaisical nature, Hardly works as The Dead Sheriff at Haunted Frontier, an amusement park. He has perfected lying low, content avoiding unnecessary irritation and labor. Hardly isn’t venturing out of his lane; he’s heading off-road into unchartered territory.

Eleanor’s questions about why is he so obsessed with helping two kids he doesn’t even know, hang over Dark Ride. Taped above the futon in the two-car garage where Hardly lives, he has a print of The Fall of Icarus. “A guy has fallen into the ocean and he’s drowning and there are all these other people around, on shore, going about their daily business. They must have heard the splash, but they just ignore the drowning guy,” Hardly says, explaining his desire to help the kids to Eleanor. “What if everyone else is ignoring them? What if they don’t have anybody but me?”

Reluctantly Eleanor helps him, as do others, including Felice Upton, a former P.I. turned real estate agent, who realizes Hardly’s obsession with this situation has put him on a dangerous path. Upton never relents, reminding Hardly that he’s in over his head.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because Berney puts Hardly through the usual paces of a shabby amateur detective, developing more confidence as he gradually gathers evidence that the children’s father, Nathan Shaw, is not just a powerful lawyer but is involved in a drug trafficking operation. Berney uses incongruities to infuse humor to balance the darkness of Hardly’s quest, and tension builds as each new piece of evidence proves Hardly’s instincts correct, revealing that the children’s abuse is part of a larger, more sinister predicament.

Hardly has found himself awakened and motivated at the idea that he might be doing something that matters for the first time in his life. This idea intoxicates him. As in Berney’s earlier work, where characters’ past traumas and vulnerabilities haunt them, Hardly was placed into foster care after his mother’s death, and he grew accustomed to lowering his expectations to stave off disappointment.

More than Hardly’s willing to admit to himself, he badly wants to be more for himself and prove that he can be more than his current circumstances. As Hardly’s competency and focus grow sharper, he’s still not without limitations. It would be easy for Berney to insert a training montage, or to reveal a newly found aptitude for self-defense to get Hardly ready for confrontations with his adversaries.

Where a lesser writer would lean into cliché, Berney continues to build upon the conflicts underlying Hardly’s white knight impulses. Unlike other fictional rough-and-tumble amateurs who follow a hunch or take on others’ problems, Hardly is still a willowy 23-year-old, now driven but still naïve and inexperienced. Hardly’s allies constantly warn him to turn over the information he’s gathered to more capable authorities. Their well-founded concerns raise tension and essential questions: Does Hardly have the good sense to get help, or does Hardly still lack the commitment to follow through?

Plaguing the reader with deep-seated worry about the fate of the characters is a hallmark of Berney’s work. In book after book, Berney effortlessly blends humor, plausible plot complications, and heart-breaking, empathetic characters in over their heads to keep readers up well past their bedtimes.

###

Tim Hennessy (@timjhennesy) is a writer and editor who lives in Milwaukee, WI. His writing appeared in Publishers Weekly, Vol. I Brooklyn, Tough, Mystery Tribune, Midwestern Gothic, and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, among other venues. He edited the Milwaukee Noir anthology from Akashic Books.